Got that feeling of tightness, pressure or fullness in your tummy? You are likely bloated, a common phenomenon that can be quite uncomfortable. Bloating can be caused by various factors but is often associated with our gut microbes fermenting undigested food in our intestines. This fermentation process creates byproducts, including gases. Too much fermentation can result in increased/excessive gas levels which can cause bloating. Those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) often experience bloating, possibly in part due to a sensitivity to certain foods and/or intestinal hypersensitivity.

Microbial dysbiosis (an imbalance in your “good” and “bad” gut bacteria) can be one of the reasons for excess fermentation and bloating. Another reason is consumption of problematic carbohydrates, i.e., FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides disaccharides monosaccharides and polyols). These carbs are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and are easily and rapidly fermented by bacteria.

Given the role of microbial dysbiosis, it may be possible to modify the composition and/or activity of the gut microbiota to relieve or reduce bloating. This can be done via the consumption of probiotics and/or prebiotics.

What are probiotics?

Probiotics are officially defined as “live microorganisms, that when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” [1]. In other words, they are good bacteria (or other microbes) that are consumed by a person to generate health benefits, such as improved digestive health. Probiotics are often found in dietary supplements and fermented foods, like yoghurt, kimchi, sauerkraut and kombucha.

Probiotics by their definition must have scientific evidence to show they provide health benefits to the consumer. The most common probiotics are from the two genera which have been studied the most – Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

-

- Bifidobacterium – members of this genus are amongst the first to colonise the gut when we are born and bifidobacteria were first isolated from the poop of breast-fed babies. Research has shown that these bacteria can help to:

-

- Support digestive health by reducing the incidence of diarrhoea particularly in infants [2,3], reducing symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [4,5], and improving bowel regularity [6,7];

-

- Produce beneficial compounds including:

-

- vitamins [8] (which we use),

- organic acids (such as lactate which balance the gut pH making it a friendly environment for other good bacteria and a hostile one to pathogens), and

- short-chain fatty acids (e.g., acetate which is used by other bacteria that generate butyrate to prevent inflammation and provide energy for the gut lining) [9].

- Lactobacillus – these bacteria are characterised by their ability to produce lactic acid as a byproduct of glucose metabolism. Lactobacillus are used during the production of sour milks, cheeses, and yoghurt, and they are also used in the manufacture of fermented vegetables (e.g. pickles and sauerkraut), beverages (e.g. wine), and sourdough breads. Lactobacillus have been shown to:

-

- Inhibit pathogens [10], reduce inflammation, improve symptoms of IBS [11], treat antibiotic-associated diarrhoea [10] and help treat and prevent vaginal infections [12].

- Produce beneficial compounds, similar to Bifidobacterium, e.g. vitamins, organic acids and short chain fatty acids.

What are prebiotics?

A prebiotic is defined by the Global Prebiotic Association (GPA) [13] as “a product or ingredient that is utilized in the microbiota producing a health or performance benefit.” Additionally, a prebiotic effect is “a health or performance benefit that arises from alteration of the composition and/or activity of the microbiota, as a direct or indirect result of the utilization of a specific and well-defined product or ingredient by microorganisms.”

In other words, prebiotics are materials that can alter the composition and/or activity of the microorganisms in the gut (or elsewhere in the body) to generate health benefits to the consumer.

Typically, prebiotics are fibres that humans can’t normally digest. Instead, once ingested, they travel to the colon intact where the gut microbes use them as food, stimulating the growth and activity of those microbes. As science in this field evolves, new types of prebiotics are emerging, including polyphenols, bacteriophage and even omega 3s.

| Commonly known prebiotics | Emerging prebiotics |

| Select fibres (i.e. Acacia) | Polyphenols (select ones) |

| Resistant starch | Bacteriophage |

| Inulin | Pectin |

| IMO | Yeast hydrolysate |

| FOS, GOS, XOS | Glucan |

| HMO | Omega 3s |

| Lactulose |

IMO: isomaltooligosaccharide; FOS: fructooligosaccharide; GOS: galactooligosaccharide; XOS: xylooligosaccharide; HMO: human milk oligosaccharide

So, can probiotics or prebiotics help with bloating?

Yes and no!

Considering probiotics first, currently, studies that have looked into the effects of probiotics on bloating (particularly in relation to IBS) show mixed results.

In a systematic review on the benefits of probiotics in people with IBS and other GI problems [14], it was found that some studies showed probiotic treatment led to a significant beneficial effect in terms of bloating/distension, while others showed no significant difference compared to placebo.

A systematic review attempts to gather all available empirical research by using clearly defined, systematic methods (i.e., search criteria) to obtain answers to a specific question.

A meta-analysis uses a statistical process of analysing and combining results from several similar studies to answer a question.

In a meta-analysis comparing probiotic and drug interventions in irritable bowel syndrome [15], probiotic use was associated with lower bloating scores, but the overall effect of probiotics on bloating was not significant.

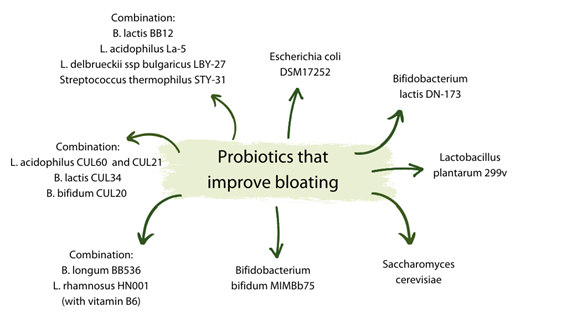

In other words, current data indicates that specific probiotics can help reduce bloating/distension (Figure 1), which makes sense given that other health benefits of probiotics are also strain-specific.

Figure 1: Specific probiotics that have been shown to improve bloating [14,15]

As with probiotics, not all prebiotics are created equal when it comes to improving bloating. In a meta-analysis investigating the effects of prebiotics and synbiotics (a combination of probiotics and prebiotics) on functional constipation [16], GOS and inulin did not improve bloating, however the combination of FOS with probiotics was found to be effective in improving bloating.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of prebiotics on IBS and other functional bowel disorders, the researchers found that prebiotics were not effective at improving bloating compared to placebo, however at low doses (≤ 6 g/day) most were able to reduce flatulence, with the exception of inulin which was found to worsen flatulence [17].

These results are not unexpected for traditional prebiotics as they are often FODMAPs, and it is common for FODMAP-type prebiotics to flare up IBS symptoms. This is supported by several studies showing that eating a low FODMAP diet can help to reduce symptoms of IBS, including bloating, constipation and abdominal pain [18,19].

Specific prebiotics do appear to have the potential to improve bloating, however. In a study on the effect of a specific GOS mixture on GI symptoms in otherwise healthy adults, 1.4 g of GOS daily led to significant improvements in bloating, flatulence and abdominal pain both from baseline and compared to placebo [20].

The easy and rapid fermentation of simple prebiotics, like FOS and inulin, is a key contributing factor to people experiencing bloating upon consumption. When fermentation happens, by-products including gases are produced. The faster this happens; the more gases are produced. This gas will eventually be used up by other bacteria, move into nearby tissue or escape out the backend, but often because this rapid fermentation creates a lot of gas and it happens early in the colon, the gas has a long way to go before it can escape, and bloating ensues.

Other prebiotics, which have complex structures, take much longer to ferment and often require several different bacteria working on different parts of the prebiotic to break it down. For example, pectin, a plant cell wall polysaccharide, is one of the most complex polysaccharides found in nature. It has large side chains with over 20 sugars and sugar linkage types (simple prebiotics may have only 1 or 2 sugars and linkage types) which must be removed by a range of enzymes from one or more cooperating bacteria before other bacteria, like the beneficial, butyrate producing Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, can access the core. This results in much slower fermentation, with gas production at a rate that is easily dealt with.

Another benefit of consuming complex prebiotics is that this can increase microbial diversity. As mentioned previously, it takes a range of different bacteria with different enzymes to breakdown complex fibres like pectin. This results in increased growth and activity of all those bacteria, not just one or two which can be the case with the fermentation of those simple prebiotics.

It is important to note that processed fibres, like some commercially available pectins, are often so processed that they lose that structural complexity which is desirable for slow fermentation. Look instead for intact pectins that have been gently processed, like those naturally present in the kiwifruit powders, Actazin® and Livaux®.

In summary, yes, some probiotics and some prebiotics can help to relieve bloating, but others don’t and/or can exacerbate the issue. Read up on the probiotics/prebiotics available to you, especially if you have IBS, and find the ones that suit you and your body best. Consider experimenting with different probiotics and prebiotics to identify the right combination and learn more about your own specific gut and it’s changing needs.

References:

- [1] Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization. Health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria. World Health Organization [online], (2001).

- [2] Chouraqui, J. P., Van Egroo, L. D., & Fichot, M. C. (2004). Acidified milk formula supplemented with Bifidobacterium lactis: impact on infant diarrhea in residential care settings. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, 38(3), 288-292.

- [3] Escribano, J., Ferré, N., Gispert-Llaurado, M., Luque, V., Rubio-Torrents, C., Zaragoza-Jordana, M., … & Closa-Monasterolo, R. (2018). Bifidobacterium longum subsp infantis CECT7210-supplemented formula reduces diarrhea in healthy infants: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatric research, 83(6), 1120-1128.

- [4] Yao, S., Zhao, Z., Wang, W., & Liu, X. (2021). Bifidobacterium longum: protection against inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Immunology Research, 2021.

- [5] Saez-Lara, M. J., Gomez-Llorente, C., Plaza-Diaz, J., & Gil, A. (2015). The role of probiotic lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria in the prevention and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and other related diseases: a systematic review of randomized human clinical trials. BioMed research international, 2015.

- [6] Magro, D. O., de Oliveira, L. M. R., Bernasconi, I., de Souza Ruela, M., Credidio, L., Barcelos, I. K., … & Coy, C. S. (2014). Effect of yogurt containing polydextrose, Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis HN019: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study in chronic constipation. Nutrition journal, 13(1), 1-5.

- [7] Chmielewska, A., & Szajewska, H. (2010). Systematic review of randomised controlled trials: probiotics for functional constipation. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 16(1), 69.

- [8] LeBlanc, J. G., Milani, C., De Giori, G. S., Sesma, F., Van Sinderen, D., & Ventura, M. (2013). Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: a gut microbiota perspective. Current opinion in biotechnology, 24(2), 160-168.

- [9] Mohan, R., Koebnick, C., Schildt, J., Mueller, M., Radke, M., & Blaut, M. (2008). Effects of Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 supplementation on body weight, fecal pH, acetate, lactate, calprotectin, and IgA in preterm infants. Pediatric research, 64(4), 418-422.

- [10] Millette, M., Luquet, F. M., & Lacroix, M. (2007). In vitro growth control of selected pathogens by Lactobacillus acidophilus‐and Lactobacillus casei‐fermented milk. Letters in applied microbiology, 44(3), 314-319.

- [11] Tiequn, B., Guanqun, C., & Shuo, Z. (2015). Therapeutic effects of Lactobacillus in treating irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Internal Medicine, 54(3), 243-249.

- [12] Chee, W. J. Y., Chew, S. Y., & Than, L. T. L. (2020). Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microbial Cell Factories, 19(1), 1-24.

- [13] https://prebioticassociation.org/prebiotic-resources/

- [14] Hungin, A. P. S., Mulligan, C., Pot, B., Whorwell, P., Agréus, L., Fracasso, P., … & European Society for Primary Care Gastroenterology. (2013). Systematic review: probiotics in the management of lower gastrointestinal symptoms in clinical practice–an evidence‐based international guide. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 38(8), 864-886.

- [15] Van der Geest, A. M., Schukking, I., Brummer, R. J. M., van de Burgwal, L. H. M., & Larsen, O. F. A. (2022). Comparing probiotic and drug interventions in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Beneficial microbes, 13(3), 183-194.)

- [16] Yu, T., Zheng, Y. P., Tan, J. C., Xiong, W. J., Wang, Y., & Lin, L. (2017). Effects of prebiotics and synbiotics on functional constipation. The American journal of the medical sciences, 353(3), 282-292.

- [17] Wilson, B., Rossi, M., Dimidi, E., & Whelan, K. (2019). Prebiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and other functional bowel disorders in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 109(4), 1098-1111..

- [18] Gibson, P. R., & Shepherd, S. J. (2010). Evidence‐based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: the FODMAP approach. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology, 25(2), 252-258.

- [19] Altobelli, E., Del Negro, V., Angeletti, P. M., & Latella, G. (2017). Low-FODMAP diet improves irritable bowel syndrome symptoms: a meta-analysis. Nutrients, 9(9), 940.

- [20] Vulevic, J., Tzortzis, G., Juric, A., & Gibson, G. R. (2018). Effect of a prebiotic galactooligosaccharide mixture (B‐GOS®) on gastrointestinal symptoms in adults selected from a general population who suffer with bloating, abdominal pain, or flatulence. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 30(11), e13440.